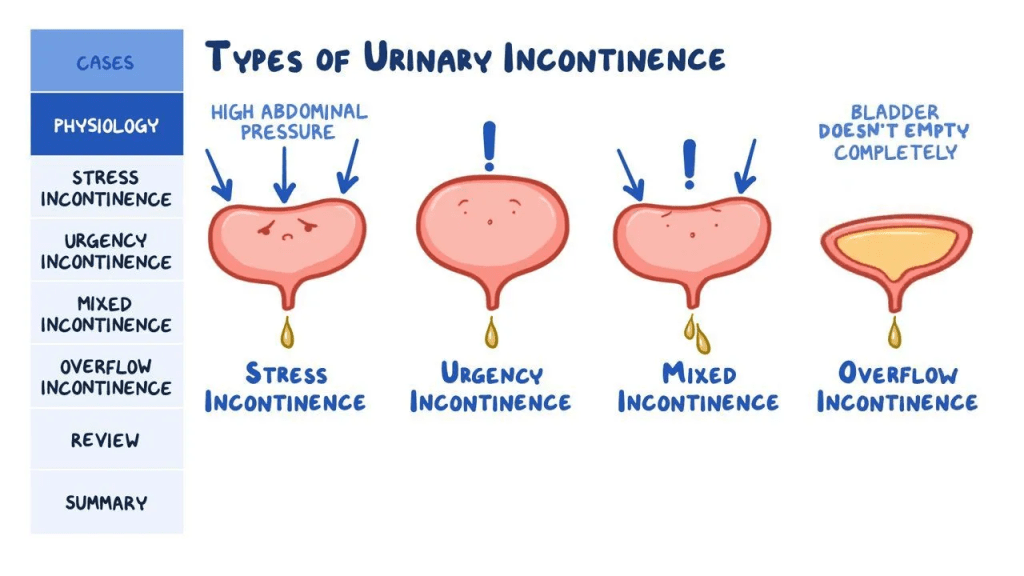

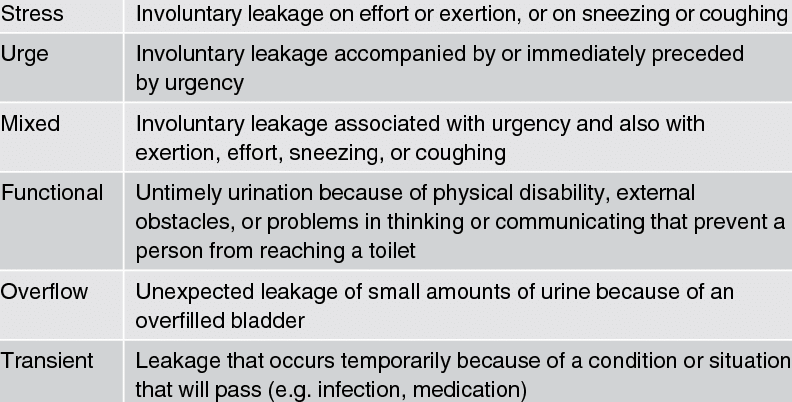

Urinary incontinence (UI) is a common condition characterized by the involuntary loss of urine. There are several types of UI, each with distinct pathophysiology, signs and symptoms, and treatment approaches.

Stress incontinence occurs when weakened pelvic floor muscles or damage to the urethral sphincter allow urine leakage during activities that increase abdominal pressure, such as coughing, sneezing, or exercise. The pathophysiology involves insufficient urethral closure pressure to counteract increased intra-abdominal pressure. Symptoms include leakage with physical exertion. Treatment focuses on strengthening pelvic floor muscles through Kegel exercises, biofeedback, and electrical stimulation. Surgical options like midurethral slings may be considered for severe cases [1,2].

Urge incontinence, also known as overactive bladder, results from involuntary detrusor muscle contractions. Pathophysiology involves neurogenic or myogenic dysfunction leading to detrusor overactivity. Patients experience sudden, intense urges to urinate followed by involuntary urine loss. First-line treatments include behavioral modifications and pelvic floor exercises. Antimuscarinic medications like oxybutynin or solifenacin are commonly prescribed. Newer options include beta-3 adrenergic agonists like mirabegron [3,4].

Overflow incontinence occurs when the bladder cannot empty completely, leading to frequent small volume leakage. Causes include detrusor underactivity or bladder outlet obstruction. Symptoms include difficulty initiating urination, weak stream, and dribbling. Treatment aims to address the underlying cause, such as alpha-blockers for prostatic obstruction or intermittent catheterization for neurogenic bladder [5,6].

Mixed incontinence involves a combination of stress and urge symptoms. Management typically starts with conservative measures for the predominant type, followed by pharmacological or surgical interventions as needed 7.

Functional incontinence results from physical or cognitive impairments that prevent timely toileting. Environmental modifications, prompted voiding, and addressing underlying conditions are key management strategies 8.

Transient incontinence is temporary and often resolves when the underlying cause (e.g., urinary tract infection, medication side effect) is addressed. Recent advances in UI management include the use of botulinum toxin injections for refractory overactive bladder, sacral neuromodulation for various types of UI, and the development of newer pharmacological agents with improved side effect profiles.

Urinary incontinence (UI) is the involuntary loss of urine, affecting millions of people worldwide, particularly women and older adults. There are several types of UI, each with distinct causes and symptoms. The main types include stress incontinence (leakage during physical exertion), urge incontinence (sudden, intense urge to urinate followed by involuntary urine loss), overflow incontinence (inability to fully empty the bladder leading to frequent dribbling), and functional incontinence (physical or cognitive impairments preventing timely toileting). Mixed incontinence, combining multiple types, is also common. While UI can significantly impact quality of life, many effective management strategies are available, and it’s important for affected individuals to seek medical advice for proper diagnosis and treatment.

References:

- Lukacz ES, et al. (2022). Urinary Incontinence in Women: A Review. JAMA, 327(13):1286-1297.

- Capobianco G, et al. (2023). Stress Urinary Incontinence: An Update on Definitions, Pathophysiology, Diagnoses and Management. J Clin Med, 12(3):795.

- Reynolds WS, et al. (2022). Diagnosis and Management of Overactive Bladder in Adults. JAMA, 327(15):1498-1509.

- Griebling TL. (2022). Overactive Bladder in Elderly Patients: Risk Factors, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Drugs Aging, 39(2):101-113.

- Jiang YH, Kuo HC. (2022). Underactive Bladder-Current Understanding of Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Management. Int J Mol Sci, 23(3):1394.

- Osman NI, Chapple CR. (2023). Contemporary Concepts in the Aetiopathogenesis and Management of Chronic Urinary Retention. Nat Rev Urol, 20(2):107-122.

- Aoki Y, et al. (2022). Urinary incontinence in women. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 8(1):43.

- Wagg A, et al. (2023). A narrative review of models of care for older people with urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn, 42(1):143-152.

- Gibson W, Wagg A. (2022). Urinary incontinence in the frail elderly. Nat Rev Urol, 19(8):484-495.

- Peyronnet B, et al. (2023). Management options for women with refractory urgency urinary incontinence: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Int Urogynecol J, 34(2):215-232.