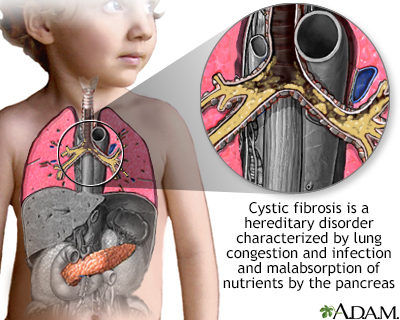

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a life-threatening genetic disorder that primarily affects the lungs and digestive system. This article provides an overview of CF, including its prevalence, epidemiology, pathophysiology, genetic transmission, clinical presentation, treatment approaches, and long-term outcomes.

Prevalence and Incidence in the US

Recent estimates suggest that the prevalence of CF in the United States is approximately 40,000 individuals. According to a 2023 study by Cromwell et al., the estimated prevalent CF population born between 1968 and 2020 was 38,804 (95% Uncertainty Interval: 38,532 to 39,065) as of 2020.The incidence of CF in the US is approximately 1/4000 live births, with variations observed across different ethnic groups. This incidence rate has been declining in recent years, likely due to increased genetic screening and counseling.

Epidemiology

CF primarily affects individuals of European descent but can occur in all racial and ethnic groups. Key epidemiological factors include:

- Age: CF is typically diagnosed in early childhood, with about 75% of cases identified by age 2.

- Gender: CF affects males and females equally.

- Ethnicity: Highest incidence in non-Hispanic whites, lower in other ethnic groups.

- Geographic variation: Higher prevalence in Northern European populations and their descendants.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of cystic fibrosis (CF) is complex and multifaceted, primarily stemming from mutations in the Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator (CFTR) gene. This gene encodes the CFTR protein, which functions as a chloride channel in epithelial cells. In CF, the CFTR protein is either absent or dysfunctional, leading to abnormalities in chloride transport across epithelial membranes. This fundamental defect has far-reaching consequences throughout the body, but particularly affects the respiratory and digestive systems.In the airways, the defective chloride transport leads to dehydration of the airway surface liquid (ASL).

Normally, the ASL consists of two layers: a lower periciliary layer that allows cilia to beat effectively, and an upper mucus layer that traps pathogens and debris. In CF, the dehydration of the ASL causes the mucus layer to become thick and sticky, adhering to the airway surfaces. This impairs mucociliary clearance, a critical innate defense mechanism of the lungs. The stagnant mucus creates an ideal environment for bacterial colonization, particularly by organisms such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The presence of bacteria triggers an intense inflammatory response, characterized by the influx of neutrophils. However, these neutrophils are often ineffective at clearing the infection and instead release proteases and oxidants that cause further damage to the airway epithelium. This cycle of infection, inflammation, and tissue damage leads to bronchiectasis and progressive decline in lung function.

In the pancreas, CFTR dysfunction results in reduced volume and altered pH of pancreatic secretions. The pancreatic ducts become obstructed with thick, dehydrated secretions, leading to damage of the exocrine pancreas. This obstruction prevents the release of digestive enzymes into the small intestine, resulting in maldigestion and malabsorption of nutrients, particularly fats and fat-soluble vitamins. Over time, the pancreatic tissue is replaced by fibrosis and fatty infiltration, leading to exocrine pancreatic insufficiency in about 85-90% of CF patients. Additionally, the progressive damage to the pancreas can also affect the endocrine function, leading to CF-related diabetes in many patients as they age.

The pathophysiology of CF extends beyond the lungs and pancreas. In the liver, defective CFTR in the biliary epithelium leads to inspissated bile and focal biliary cirrhosis in some patients. In the reproductive system, most males with CF are infertile due to congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens, while females may have reduced fertility due to thickened cervical mucus. In the sweat glands, the inability to reabsorb chloride in the sweat duct results in the characteristic elevated sweat chloride levels used in diagnosing CF. This comprehensive understanding of CF pathophysiology has been crucial in developing targeted therapies and improving patient care.

Genetic Transmission

CF is an autosomal recessive disorder. Key points include:

- Both parents must be carriers of a CFTR mutation for a child to be affected.

- If both parents are carriers, there is a 25% chance of having a child with CF.

- Over 2,000 mutations in the CFTR gene have been identified, with F508del being the most common.

Signs and Symptoms

Common signs and symptoms of CF include:

- Respiratory: chronic cough, recurrent lung infections, shortness of breath

- Gastrointestinal: malnutrition, fatty stools, constipation or intestinal obstruction

- Reproductive: infertility (especially in males)

- Other: salty-tasting skin, clubbing of fingers and toes

Treatment

Treatment for CF is multifaceted and aims to manage symptoms and slow disease progression. While these treatment options might be effective today, treatment options change as we learn more about each disease process.

- Airway clearance techniques and inhaled medications to thin mucus

- Antibiotics to treat lung infections

- CFTR modulators (e.g., ivacaftor, lumacaftor) to improve CFTR protein function

- Pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy

- Nutritional support and vitamins

- Lung transplantation for end-stage lung disease

Long-term Outcomes

With advances in treatment, the prognosis for individuals with CF has significantly improved:

- Median predicted survival has increased to over 50 years in developed countries.

- Quality of life has improved with new therapies and better management strategies.

- Transition to adult care has become an important focus as more patients reach adulthood.

- Psychosocial support is crucial for long-term well-being.

Conclusion

Cystic fibrosis remains a complex, life-shortening genetic disorder. However, advances in understanding its pathophysiology, improvements in treatment options, and the development of CFTR modulators have dramatically improved the outlook for individuals with CF. Ongoing research continues to push the boundaries of CF care, offering hope for further improvements in quality of life and longevity for those affected by this challenging condition.

References

- Cromwell EA, et al. Cystic fibrosis prevalence in the United States and participation in the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry in 2020. J Cyst Fibros. 2023;22(3):454-461.

- Middleton PG, et al. Elexacaftor-Tezacaftor-Ivacaftor for Cystic Fibrosis with a Single Phe508del Allele. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(19):1809-1819.

- Nichols DP, et al. CFTR modulators: The changing face of cystic fibrosis care. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(8):979-984.

- Mayer-Hamblett N, et al. Advancing clinical development pathways for new CFTR modulators in cystic fibrosis. Thorax. 2020;75(6):520-525.

- Burgel PR, et al. Future trends in cystic fibrosis demography in 34 European countries. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(1):1900704.

- Ronan NJ, et al. Current and emerging comorbidities in cystic fibrosis. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(9):885-895.

- Rayment JH, et al. Lung clearance index to monitor treatment response in pulmonary exacerbations in preschool children with cystic fibrosis. Thorax. 2018;73(5):451-458.